PAKISTAN – ON THE EDGE

OPINION | NOVEMBER 5 2019. BY MOHAMMED RIZWAN. PRAGMORA INSTITUTE FELLOW

Pakistan is ranked as the 23rd most fragile state in the world, and falling. How did Pakistan get here, and is there any viable remedy to cure its ailing economy?

The Fragility of the Pakistan State

In the 2019 Fragile States Index, Pakistan is ranked as the 23rd most fragile state in the world, placing it in the ‘alert’ category – better the ‘red alert’ countries but more fragile than North Korea, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya and Venezuela. War-ravaged Yemen sits at the bottom of the list of 178 countries.

The indicators employed to rank the fragility of a state encompass a wide range of pillars on which the functionality of the state depends and stands. These indicators include security apparatus, state legitimacy, factionalized elites, group grievances, economy, economic inequality, demographic pressure, human rights, public services, flight of capitals and humans, external intervention, and refugees. Pakistan scores poorly on each and every one of these indicators, and scores particularly poorly on capital flight and brain drain. Further, the Index shows a sharp rise in state fragility in Pakistan over the past 5 years.

How did Pakistan get here? Is a miraculous escape from a total breakdown of the state possible?

How Pakistan Got Here

Pakistan was established in 1947, carved out by British colonial rulers on the basis of a very confused, sketchy and bizarre idea that conceptualized Hindus and Muslims as two distinct nations and therefore established one nation state for each despite the fact that Muslims and Hindus had shared centuries of occupying the same land since the Muslim invasions from central Asia and Iran. The idea of a separate state (Pakistan) for Muslims was not popular until after provincial elections of 1945-46 when the party of the founder of Pakistan Muhammed Ali Jinnah won electoral legitimacy to speak for Muslims of India. The large region of Balochistan was never consulted because it did not have a status of province then, although it was promised a referendum after independence. Strikingly, the most vocal calls for independent state for Muslims came not from Muslim-majority areas, barring Bengal, but from a Muslim minority province Uttar Pradesh which was deeply embedded in India and had no chance to become part of the envisioned Muslim Pakistan.

Although the area of the proposed Muslim Pakistan was already home to numerous distinct nations – Pashtuns, Balochis, Sindhis, Punjabis, Bengalis and Kashmiris, it was being sold as a single national entity to justify the two-state two-nation solution (India and Pakistan) to the world. This unifying factor was wholly invented and the new state was dubbed “Muslim Pakistan” in contrast to “Hindu India”.

The founding of Pakistan faced challenges from its very conception. The ruling elite were composed of land owners plus the newly created military. These two vested groups cemented the ‘Muslim Pakistan’ fiction as it served as an insurance policy for their continued rule. In truth, the Bengali majority combined with Pashtuns, Sindhis and Balochis could have snatched electoral power on the basis of numbers alone. Soon after independence, the military, with help of complicit politicians, warned of threats from India, which took the centre stage and led public discourse. This fear mongering made the military relevant and indispensable in the early years and turned the state into a security state rather than the social welfare state the people were promised. Thus a 70-year military-led dispensation emerged that first coerced and marginalised all other nations except Punjabis and complicit Sindhis, and later fought and won internal power struggles by raising the bogey of the constant threat from India. With the help of India, Pakistan’s Bengalis seceded in 1971 after 25 years of social and economic exploitation and political marginalisation despite their majority status to form the independent non-contiguous state of Bangladesh.

The new Pakistan without its eastern wing (Bangladesh), did not put an end to Pakistan’s internal fragility. A new internal struggle emerged between the landed elite and the military, and after the Afghan Jihad appeared in 1980, the military became the single most powerful entity of the state – assuming the self-conferred role of state of Pakistan. As a state completely focused on security, the perceived threat from India (Pakistan started three out of four wars with India and lost all of them) has served the military well in establishing its stranglehold on power.

Economy – the decisive factor in survival

We have to travel back a bit in history to understand the economy of today as it hasn’t changed much in 73 years. Pakistan was born as resource depleted and impoverished country. Soon after its inception, founder Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who had lived life in Bombay as a lawyer and hailed from Indian state of Gujrat, asked the United States for $2 billion dollars in financial aid threatening that without this aid Pakistan might consider joining the Soviet camp in the Cold War. Though the U.S. administration refused, this ‘aid for allegiance,’ this threat continues to this day, often with success. As early as 1949-50 Pakistan offered to send troops to support the U.S. in the Korean War in exchange for aid and military equipment, and then in 1956 joined U.S. orbital alliances against Soviet expansion – SEATO and CENTO. From 1957 to 1959, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower embraced Pakistan as a stalwart ally against the communist Soviet Union and China as India moved to Soviet camp in the post-World War II Cold War era. Subsequently, Pakistan’s annual budget has depended on bilateral US aid along with loans from multilateral financial institutions backed by American goodwill and good offices.

Pakistan’s failure to build effective political institutions from the very beginning resulted in a failure to build economic institutions and an efficient tax collecting agency. Right from the start there was no effort to build industrial base a few attempts at crony capitalism in 1960s notwithstanding. In the absence of any manufacturing base – cottage or large-scale – there was nothing to export apart from a few billion dollars worth of earnings from raw crops like cotton and jute. There were no serious attempts to build public services like education, health and infrastructure as whatever the money was coming from abroad, mostly as loans, was spent on lavish non-developmental expenditures, paying annual interests on loans and defence. The state focused on political conflicts, internally with elite civilian groups and externally with India that provided them their basis for legitimacy.

Since its establishment, Pakistan’s economic model hasn’t changed a bit – barring introduction of two devastating factors. One, military controls all kinds and colours of sources of private and public wealth (the miniscule formal private sector has also become arm of military’s financial empire) and two, badly exposed at world stage all the donors including the principal United States have pulled back from their decades old policy of funding and sponsoring the state / military due to variety of constraints and geopolitical factors.

The Pakistan Economy today

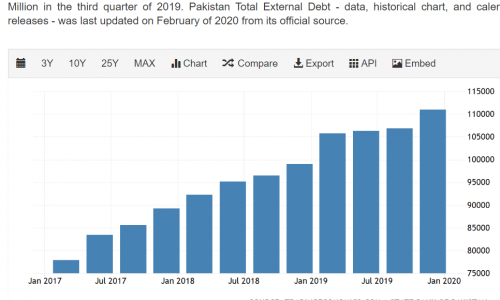

With respect to the formal economy, Pakistan collects roughly $25 billion dollars in revenue each year from all sources (direct taxes, indirect taxes, customs, duties, levies, etc). Its annual expenditure is $38 billion resulting in a huge fiscal deficit of roughly $13 billion. Its current account deficit, not included in GDP (the gap between exports and imports), is more than $14 billion. Out of the Rs4000 billion that the country earns, $12.4 billion go towards repayment of loans on country’s ever ballooning external and internal debt of roughly $107 billion[i] dollars. More than $11 billion is spent on defence and security. That leaves the space of only $1.6 billion in the budget to run the federal governments, five provincial governments, and public sector development programmes like health, education, infrastructure and so on for a country with 220 million people. Obviously, it’s not enough. So every year there is a wait for tranches from bilateral and multi-lateral donors to be doles out to make up for the $ 13-14 billion dollars budgetary deficits.

When each tranche arrives, the priority is deduction of non-development expenditures (running the huge top-heavy government – salaries, pensions, vehicles, fuel allowances, embassies, foreign trips, etc.), with whatever is left is doled out to provinces to run the public sector development. Last year, only $3 billion dollars were left to spend on public services.

Now the fundamental question. Why is Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio is only 11%–one of the lowest in the world and debt to GDP ratio is around 91%, one of the highest in the world? The answer is simple: Out of 220 million people, only 800,000 file taxes, only 500,000 actually pay them, and only 70,000 small, medium and large private sector businesses pay taxes. People don’t pay taxes because they never did and the state never seriously tried to collect them. Since day one, it was a security state run by the men in uniform rather than the representative civilian stat, so the issue of public spending and public welfare was never the national priority. As long as defence is strong and Pakistan is building missiles and not bowing to India, it was a small sacrifice, the people were always told. But it is the common person who sacrificed while generals, their subservient bureaucrats, and crony politicians became richer and richer.

In this context, a large black economy emerged and thrived which is reportedly the same size as the actual economy. The estimated size of Pakistan’s economy including both formal and informal is $280 billion. This black economy found a natural partner in Pakistan’s military that always needs money to fund its various projects. [ii]

The socio-political-economic-security structure of the Pakistani state worked fine as long as its main sponsor – the United States – was happy. Under President Donald Trump this has changed. After a lengthy Afghan Strategic Review the United States decided to end the ‘aid for alliance’ charade as they realised fully as had the previous Bush and Obama administrations that the U.S. was actually fighting the Pakistan military and its intelligence agencies in Afghanistan. Pakistani forces in Afghanistan were killing American soldiers in Afghanistan, along with Al Qaeda militants and it was money from the U.S. that was used for these Pakistani operations and to fund and arm the Taliban. At the same time, Pakistan faces rising geopolitical and economic tensions with China who has called for a strategic alliance with India.

Since the U.S. stopped bilateral aid and coalition support fund for the Pakistani military and the multilateral Financial Action Task Force tied future IMF and World Bank assistance to cutting ties with Jihadis and the Taliban, the Pakistani state has knocked at every door in the neighbourhood that they could – China, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, Qatar – but could not get even enough money to pay the imports bill for one year. The only choice now is for Pakistan once and for all to close down its ‘Jihad project’, end support for the Taliban, and verifiably end its Jihad pipeline that runs from Kabul to Delhi. That may gradually result in winning back the trust of regional neighbours and the United States. This work is now in progress.

There are no easy remedy for Pakistan’s ailing economy. There doesn’t seem to be a long-term solution. The best one can hope for is short-term tactics that yield good results quickly. In the fiscal 2018-19 year, Pakistan only scrapped through to make budget barley managing loan payments deadlines thanks to last-minute cash injection from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. But this year apart from two billion dollars conditional budgetary support from IMF and expected cash from World Bank, Pakistan is on very short leash. The IMF has placed stringent conditions on continued support of $6 billion dollars for four year program on verifiably severing ties with Jihad financing and on introducing vital economic reforms—but such reforms are likely to end subsidies and slash the defence budget. International donors have forced Pakistan to float, thus far an artificially pegged currency and sell almost all loss-making state enterprises. Even if Pakistan complies, there is little breathing space in the absence of waning revenues, due to rising inflation, topped-up interest rates and fast closure of already inadequate industrial sector.

Lately, the state pinned their hopes on a proposed $62 billion investment from China for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC was supposed to lay power and communication infrastructure across Balochistan Province but in reality it was just a road to Gwadar Port that China wants desperately to build a naval base – at the mouth of Gulf and Strait of Hormuz from where 60 per cent of world’s energy and goods shipping pass through. With the geostrategic landscape shifting at a great pace, the Pakistan military faces a choice to decide quickly and decisively whether their long-term strategic ties with China will alienate their old principal patron the United States.

The only choice for the state at the moment is to increase income and decrease expenditure. One way to increase income in the short-term is for citizens to start paying taxes, but under the circumstances when the rupee has lost 34% against the dollar since January 2018 and the official inflation rate is approaching 15%, people will not have anything with which to pay taxes. The only remaining course of action is the imposition of indirect taxes on utilities, fuel and other essential items like imports. This course is fraught, however, with the spectre of widespread political unrest which would be difficult to manage as political cohesion in the country is already at its lowest ebb. Provinces have not been paid for development for the last two years and it will be very very difficult to pacify them in the absence of any broad political consensus. The political consensus on economy is hard to achieve as provinces insist on decentralization of economy and to have what they earn after paying federal taxes. However, this demand is unacceptable for the military as it would diminish their role in economy and thwart their direct access to the exchequer.

There are no easy solutions. And there may be no solution at all to revive the Pakistani economy and stabilize this increasingly fragile state.

Prognosis

Though Pakistan is precariously placed on all 12 indicators for a fragile state and is placed in alert category, it’s economy and unviability and fragmentation of military that can trigger a collapse faster than anyone could think of. There is a tiny flicker of light at the end of the tunnel but for that to happen state along with people of Pakistan will have to immediately change the way they lived for generations. If army withdraws from all aspects of public life and governance and people of Pakistan, waking up to reality, stop living in echo chamber and a bubble, start building institutions and start paying taxes then maybe that flicker becomes a beacon at the end of the tunnel. But this possibility exists only for argument’s sake – a scholar’s fantasy. The chances for this to happen are miniscule. The possible scenario can produce Balkanization of Pakistan with multiple regions on the west bank of Indus and in south becoming completely lawless and ungovernable in the immediate aftermath. Under this scenario, if the people of region are lucky, these breakaway regions could become viable political and economic entities in the longer term. Saudis, Gulf states and maybe Chinese who share long western borders with Pakistan could play a role in managing the spillover.

However, the problem of nuclear arsenal (keeping them secure in the event of any eventuality) will be a tough one to manage. When Soviet Union broke up, Russian federation was there to take care of things. In case of Yugoslavia and Balkans, Europe rushed to manage the spillover as the mess was created right in the middle of backyard but in case of Pakistan there is no internal state structure left that could keep the flag flying.

The immediate worst case scenario would be, owing to fragmentation and ideological groups in the army, the country descends into a bloody civil war with civilian proxies of each of these military groups involved in this fight. In this case the situation will resemble Afghanistan since 1990 and may result in millions of deaths. Since the country is situated bordering Iran in a close proximity to Yemen, Iraq and Afghanistan, the situation will be a nightmare for the US who controls sea lanes of Gulf and Indian ocean, China that borders Pakistan and India, the immediate neighbour. And this huge land mass that stretches from Indian ocean to Syria and Mediterranean would be a giant lawless swath comprising several failed states. Across the red sea there is Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea and Libya, the states that have already failed. –

[ii] Siddiqa, Ayesha Military Inc OUP 2007, pp 151-pp 166 (Civilian-Military politico-economic integration)

(The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Pragmora Institute)

_____________________________________________

READ PART TWO: THE STORY OF PAKISTAN IS THE STORY OF ITS MILITARY